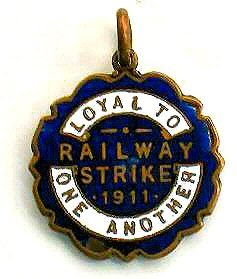

Llanelli Memories of the Railway Strike

Although there has been little official recognition of the Llanelli Railway Strike,

there is a rich vein of folk memories. Many families have one story or another.

My grandmother used to tell me about how police dug up the back gardens of

houses in Llwynhendy, looking for looted produce.

Although there has been little official recognition of the Llanelli Railway Strike,

there is a rich vein of folk memories. Many families have one story or another.

My grandmother used to tell me about how police dug up the back gardens of

houses in Llwynhendy, looking for looted produce.

She also recalled a speech from the leader of the local railwaymen, John Bevan, who stood on the track by the Eastern crossing and insisted that no trains were going to pass except over him first. My great-aunt, Harriet Ann Thomas, a worshipper at Dock Chapel, used to take great pleasure in telling the story of a looting crew who made a huge effort rolling a giant barrel of beer up Bigyn Hill, only to find out, as they thirstily tore the lid off, that it was vinegar. Harriet Ann was always firmly anti-alcohol.

For most people Llanelli 1911 means the riot, with its looting and later on its raids and arrests. As it happens, court and prison records are sometimes the only way working-class activism is registered. In any event, we should understand one thing about riot: it has been part of the political process in Britain and elsewhere for centuries. Martin Luther King called it “the voice of the unheard”. And direct action works. Look at the Rebecca Riots of the 1830s, which got rid of the tollgates, or the Poll Tax Riots of 1990, which effectively toppled Margaret Thatcher.

Yet the riot was only one part of what happened in Llanelli in 1911. It was first and foremost a railway strike, and one which scared the living daylights out of the authorities. The rail workers were low paid – poverty stalked the streets of Llanelli in 1911, despite the expanding economy. Infant mortality was high. In 1911, 113 babies died in Llanelli. Yet the railway companies were making record profits and handing out substantial dividends to their shareholders. This money could have gone some way to giving railworkers – who worked between 60-72 hours each 6-day week – a modest increase in take-home pay. The revolt in Llanelli 1911 was in many ways a revolt against these conditions and against such inequality.

It was also a revolt against the authorities, who had showed that, in order to protect the profits of the railway companies, they were prepared to shoot people dead in their own back gardens.

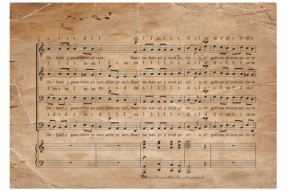

Over the next few weeks, I hope to demolish some more myths about 1911. I shall also be looking at how our song “Sospan Fach” keeps the memories of 1911 alive.

“Sosban Fach” is Llanelli’s signature-tune. It’s more than a song, it’s an

expression of a certain attitude. A quirky, determined, ‘ornery’ sense of

identity. Without straying into Private Eye’s Pseud’s Corner, I really think it

sums up so much about the town’s character. And the song has, I believe,

been a channel for popular memory and consciousness. Even though there has

been official silence about the strike and uprising of 1911, “Sosban Fach” has,

through some of its words, encoded and transmitted traces of the dramatic

events of those days.

“Sosban Fach” is Llanelli’s signature-tune. It’s more than a song, it’s an

expression of a certain attitude. A quirky, determined, ‘ornery’ sense of

identity. Without straying into Private Eye’s Pseud’s Corner, I really think it

sums up so much about the town’s character. And the song has, I believe,

been a channel for popular memory and consciousness. Even though there has

been official silence about the strike and uprising of 1911, “Sosban Fach” has,

through some of its words, encoded and transmitted traces of the dramatic

events of those days.

I will return to this. But there are many other strands which connect this song to the heady, insurrectionary days of 1911. There was an euphoric, carnival atmosphere on the all-night picket lines during the first night of the strike, before the soldiers arrived. There were speeches, tap-dancing contests and a mock election.

And the pickets and demonstrators sang “Sosban Fach” as they engaged in the pushing and shoving against police lines that anybody on the 1984-5 miners’ picket lines will be familiar with. In fact, at Llanelli serious scrummaging techniques were employed, the police being defeated on a number of occasions. And all to the tune of “Sosban Fach”!

The magistrate who called in the troops who fired the fatal shots, and was also, it turned out, a shareholder of the Great Western Railway Company, had his shop trashed and looted on the Saturday night. And as the crowds carted off the groceries they, too, were singing “Sosban Fach”. It was the song of choice of the uprising!

Furthermore, one of the men who was shot and killed – John John, known as “Jac” – was both a tinplate worker and a rugby player, thereby having two connections to the song. The “Sosban” – the iconic symbol of the town – expressed the burgeoning confidence of the expanding tinplate industry. By 1911 there were 107 tinplate mills in the area. John John, who lived with his family in Railway Terrace, worked at Morewood’s tinplate mills. During the strike of 1911 the tinplaters turned out in force in support of the more poorly paid railway workers.

“Jac” was also a talented rugby player. A centre for the Oriental Stars team, great things were expected of him on the Stars’ tour of France later that autumn.

But the clearest connection of “Sosban Fach” to the 1911 uprising is the verse that goes: “Dai bach y soldiwr/ A chwt ei grys e mas” – “Little Dai the soldier/ And his shirt tail hanging out”. This verse only appears after 1911 and is surely a reference to the military intervention and the shootings, which had such an impact on popular consciousness. It has been suggested that “Chwt ei grys e mas” is a reference to the fact that the soldiers were surprised by the strikers and had not had time to dress properly. Could there even be a memory here of the soldier who refused to fire on the crowd?

Even though the authorities wanted to airbrush the Llanelli uprising of 1911 from history, the folk traditions of story-telling and popular song continue their narrative regardless, transmitting shared experience through their own collective channels. For my money, “Sosban Fach”, with its tones that can be sometimes martial, sometimes sad and sonorous, is the anthem of 1911.