Working for the Revolution

The question of syndicalism is central to understanding what went on in Llanelli in August 1911. Not because there were specific syndicalists who were active in Llanelli during the strike, but because for a few brief years, syndicalism cut with the grain of the experience of many workers, not just in Wales but across Great Britain and, indeed, the world. The great British class confrontations of this time, whether in Llanelli, Liverpool or Hull, are classic revolutionary syndicalist scenarios.

The question of syndicalism is central to understanding what went on in Llanelli in August 1911. Not because there were specific syndicalists who were active in Llanelli during the strike, but because for a few brief years, syndicalism cut with the grain of the experience of many workers, not just in Wales but across Great Britain and, indeed, the world. The great British class confrontations of this time, whether in Llanelli, Liverpool or Hull, are classic revolutionary syndicalist scenarios.

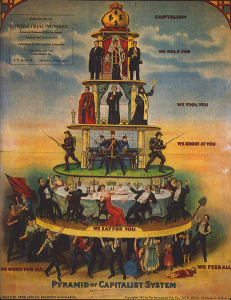

The French word syndicalisme simply means trade unionism. But the syndicalists had a quite specific take on trade unions: they wanted to turn them into organising centres for class struggle and revolution. The syndicalist poster on the left depicts the capitalist system and the way it keeps workers in their place. Syndicalists quite correctly saw the power which could be wielded by organised workers, fighting independently and for themselves. They also saw the tendency of the so-called ‘leaders’ of the labour movement, whether in parliament or the unions, to muzzle and deaden that movement’s fighting edge.

At its peak, British syndicalism influenced many. Sales of the Industrial Syndicalist Education League’s paper, The Syndicalist reached 20,000 in 1912 and two conferences organised by the paper represented 100,000 workers.

But there were weaknesses too. The syndicalists failed to create a political dimension, seeing their industrial strategy as all-encompassing, and distrusting ‘politics’. This meant that they could not engage with other radical movements such as the fight for women’s emancipation or the Irish struggles. Crucially, it meant they had not built up a network of activists who could co-ordinate resistance as world war approached.

But, for those all too brief years before the war, syndicalist scenarios were fought out across Britain. It is this which accounted for the influence of revolutionary syndicalism – not that workers read about and absorbed Marxist and anarchist theories, but that they found themselves engaged directly in class battles which proved the truth of those ideas and strategies.

Bob Holton, the historian of British syndicalism, and Deian Hopkin, who wrote the first serious assessment of Llanelli 1911 (and who will be speaking in Llanelli in August at the Railway Strike Forum) mention the phenomenon of “proto-syndicalism”. Workers on the mass picket or in the streets shared “the aspirations of syndicalism without articulating, or even being aware of, its theoretical framework.” Workers learned from their own experience that the state was on the side of capital, that their leaders could not be relied upon and that solidarity and direct action worked. Could trade union consciousness become revolutionary?

Who were the syndicalists?

Syndicalists like Tom Mann (pictured below) and Ben Tillett (pictured bottom of page), who was the star speaker at the Llanelli mass protest a month after the shootings, were part of an international revolutionary movement. Revolutionary syndicalism swept many parts of Europe, the USA, Latin America and Australia between the 1890s and the 1920s. Its aim was to overthrow capitalism through industrial class struggle and build a new socialistic order free from oppression, in which workers would be in control. Change would come neither through parliamentary pressure nor a political insurrection leading to state socialism, but would be achieved through direct action and the general strike, winning workers’ control over the economy and society. Syndicalists concentrated on the revolutionary potential of working-class organisation, notably the trade unions. The unions would serve both as organisers of class warfare and as the nuclei of the post-revolutionary society.

Change would come neither through parliamentary pressure nor a political insurrection leading to state socialism, but would be achieved through direct action and the general strike, winning workers’ control over the economy and society. Syndicalists concentrated on the revolutionary potential of working-class organisation, notably the trade unions. The unions would serve both as organisers of class warfare and as the nuclei of the post-revolutionary society.

There is some debate about how significant a factor syndicalism was during the Great Unrest of 1910-1914. Although there was no evidence of the involvement of named syndicalists among the railworkers of Llanelli in the strike of 1911, the dockers’ leader Ben Tillet was active in the area, standing (unsuccessfully) in Swansea in the general election of 1910. He was the star speaker at the Llanelli rally in September 1911, where he said: “Let the labourer rise in his wrath, in his dignity, in his mightiness and say: ‘I will be a man, my children shall be fed, my manhood shall be established or, by God, I will fight the powers that oppress me.”

“Let the labourer rise in his wrath, in his dignity, in his mightiness and say: ‘I will be a man, my children shall be fed, my manhood shall be established or, by God, I will fight the powers that oppress me.”

There was also a strong syndicalist presence on the national railway network, and among many of the miners of south Wales, like Noah Ablett, who, as part of the Unofficial Reform Committee, wrote the influential pamphlet The Miners’ Next Step in 1911, calling for rank-and-file control of a fighting union. Disillusionment with Labour in parliament was feeding the growth of direct action. A syndicalist leaflet called on strikers in the small Bristol coalfield to: “Fight for yourselves…Leaders only want your votes; they will sell you. They lie, Parliament lies and will not help you, but is trying to sell you…. Such sentiments had real resonance for British workers in 1911.